Endoscopic Lumbar Discectomy

Endoscopic (or ‘key hole’) discectomy is the most minimally invasive way of removing a disc herniation from the lumbar spine. By combining tiny incisions (usually less than 1 cm) with high-definition endoscopic visualisation, endoscopic lumbar discectomy can be performed with minimal disruption to normal tissues and often without the need for general anaesthesia. Patients can often go home the same day, and return to normal function sooner than any other method.

Indications

Disc herniations in the lumbar spine can lead to sciatica, or ‘nerve’ pain’ running down the back, side or even the front of the leg. Sciatica may be associated with numbness, pins and needles, and even weakness. Fortunately, most cases settle by themselves. However, if symptoms persist or worsen despite physical therapy, medications and injections, surgery to remove the disc herniation may be indicated. In some instances, particularly if weakness, or problems with bladder or bowel function are present, surgery may need to be urgently. Reasons why people might choose the endoscopic method include patients who do not want to have (or are unfit to undergo) a general anaesthetic (i.e. GA), if they want to be discharged from hospital sooner, or resume normal activitiesfaster, including work. Not all cases are suitable for endoscopic surgery, and you, along with your surgeon, will decide what is best for you.

Procedure

Endoscopic spine surgery is usually done with the patient lying on their stomach. Often, surgery can be performed with the patient awake, i.e. not needing general anaesthetic. This allows real-time monitoring of the patient’s symptoms, in addition to eliminating the potential side effects of general anaesthesia.

A tiny incision (usually less than 1 cm) is made in the back, through which the desired level is precisely targeted using a series of tiny dilators with minimal disruption of normal tissues. Through a high-definition endoscope, specialised instruments are used to remove the disc herniation, thereby taking the pressure off the nerves and relieving you of your sciatica. Only the part of the disc that has herniated or ‘ruptured’ is removed, leaving the rest intact.

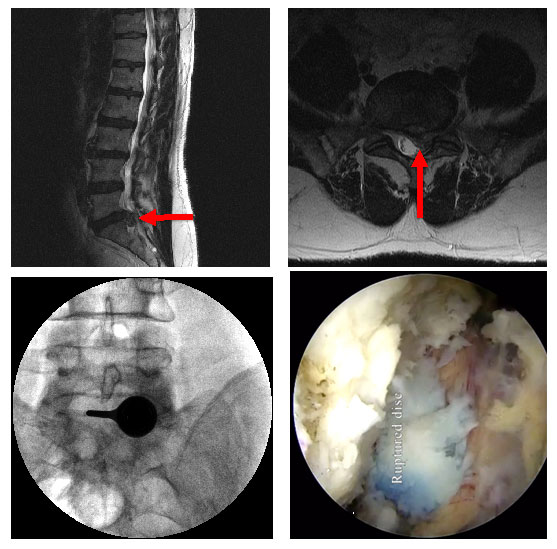

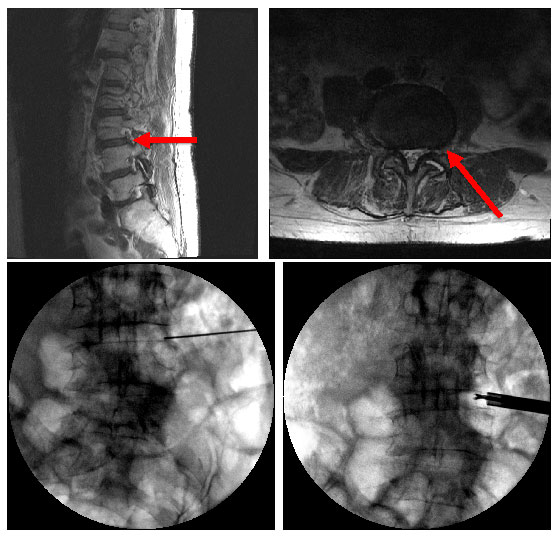

There are two main ways of accessing the disc herniation endoscopically. One is through the middle of the back, termed ‘interlaminar’ (i.e. between the laminae, which are the plates of bone that form the roof of the spinal canal). The other is through the side of the back, termed ‘transforaminal’ (i.e. through the side channels where the nerves come out). Which approach is taken depends on where the disc has herniated, with ones more towards the centre usually tackled through the interlaminar route, while ones more out to the side through the transforaminal route.

Figure 1. Interlaminar (through the middle of the back) endoscopic lumbar discectomy, with MRI before surgery (top left and right), X-rays done during surgery showing the endoscopic port in position (bottom left), and endoscopic view of a large ruptured disc (bottom right).

Figure 2. Transforaminal (through the side of the back), with MRI before surgery (top left and right), and X-rays done during surgery showing the how the disc is precisely targeted (bottom left) and special tools used to remove the disc herniation (bottom right).

Postoperative instructions

Every patient’s recovery is different. However, patients can often go home the same day after endoscopic lumbar discectomy. Walking can usually resume right away, and driving within a week or two. Timeframe for return to work depends on the type of work you do. Most people should wait around 6 weeks before doing more strenuous activity to give the body enough time to heal. During this time, you should avoid BLT (i.e. bending, lifting, twisting), and any other activities that hurt.

Adhering to the post-operative instructions provided by your surgeon is important to promote healing and reduce possible complications.

Risks and complications

Like any operation, there are risks of infection and bleeding, although these are very low (and may be even lower in minimally invasive surgeries like endoscopy).

As is the case after any discectomy, a small proportion of patients may develop another (or recurrent) disc herniation due to an existing weakness or ‘tear’ in the covering of the disc, and may require more surgery.

There is always a chance that the pain, numbness, pins and needles, or weakness will not completely go away.

The chance of nerve injury, leading worsening pain, numbness, pins and needles, weakness, bladder or bowel issues, or problems with sexual function is very rare.

Other risks include spinal fluid leak, scarring, and removal of too much overlying bone leading to instability (extremely unlikely after endoscopic surgery, as minimal to no bone removal is usually necessary).

Anaesthetic and medical risks include heart or breathing issues, chest or urine infections, and blood clots in the legs (termed DVTs, which may travel to the lungs, causing PEs), all of which are extremely unlikely after endoscopic lumbar discectomy.

Advantages

- Tiny incision (< 1 cm)

- Minimal disruption to normal tissues

- Surgery can often be done without general anaesthetic

- Less pain after surgery

- Less requirement for strong pain-killers after surgery

- Lower rates of infection

- Shorter stay in hospital

- Faster recovery time, including earlier return to work